I asked ChatGPT about Aristotle—not just his ethics, but how his thinking might resonate in today’s world.

Taking into account the context of ancient Greek society, can you explain Aristotle’s philosophy in detail? Also, please clarify the differences between Plato and Aristotle.

Finally, I’d like to know which major philosophers were influenced by Aristotle and how their ideas reflect his legacy.

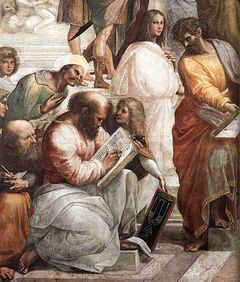

Aristotle lived in the 4th century BCE, in a period when Athenian democracy was in decline and the Macedonian empire was rising. Unlike Socrates or Plato, Aristotle was born in Macedonia and entered Athens as a somewhat external observer. He studied under Plato, but eventually broke from his teacher’s idealism and founded his own school, the Lyceum.

Where Plato looked upward—to a realm of perfect Forms—Aristotle looked outward, to nature. He believed that truth is not found in some other world, but in this one. His philosophy was grounded in observation, classification, and causality.

Believed in eternal, abstract “Forms” that exist beyond the physical world. Sensory reality is only a shadow of the true, ideal realm.

Rejected separate Forms. Saw reality as made of concrete substances with purposes and causes. Truth is found through empirical study.

Aristotle introduced a famous framework for understanding reality: the four causes. He believed that to understand any object or phenomenon, we must ask four types of questions.

Aristotle applied this logic to everything—biology, politics, ethics, literature. He believed every living thing has a telos, or natural end. A good human life is one that fulfills its purpose by developing reason and virtue. Politics, too, must be structured to allow humans to flourish. “Man is a political animal,” he wrote—not as a slogan, but as a natural truth.

His work also founded formal logic, particularly the syllogism, and contributed deeply to biology, ethics, rhetoric, metaphysics, and political theory.

Philosophers Influenced by Aristotle

Blended Aristotelian philosophy with Christian theology. Used the four causes to explain nature and God. Emphasized reason and natural law.

Jewish thinker who fused Aristotle with Jewish theology. Argued for a rational God and the compatibility of science and faith.

Aristotle transformed philosophy into a methodical study of the real world, grounded in structure and purpose. If Plato envisioned a perfect reality beyond this one, Aristotle gave us the tools to understand and work within the one we have.

I’d like to understand more deeply what Aristotle meant by “virtue.” What is virtue according to his philosophy, and how does it relate to human nature and happiness?

For Aristotle, virtue (aretê) is not an abstract ideal or a divine command—it is something practical, embodied, and deeply human. Virtue is the quality that enables something to fulfill its function well. A knife is virtuous if it cuts well. A person is virtuous if they live in accordance with reason, which Aristotle saw as the distinctive function of human beings.

In this framework, ethics is not about rules or punishment. It’s about developing excellence in being human.

Concerned with character and emotion. Developed through habit. Examples: courage, generosity, temperance.

Concerned with reasoning and thought. Developed through instruction. Examples: wisdom, understanding, prudence.

At the heart of Aristotle’s ethics is the idea of the Golden Mean. Virtue lies not in extremes, but in the balanced middle between two vices.

But this balance is not the same for everyone. Aristotle emphasized that virtue is context-dependent. What is generous for one person might be excessive for another. Ethical living requires practical wisdom (phronesis)—the ability to judge well in real situations.

Virtue is also tied to eudaimonia, often translated as “happiness” or “flourishing.” For Aristotle, a good life is not a life of pleasure or wealth, but one of rational activity in accordance with virtue, sustained over a lifetime.

Development of virtue through habit and reflection

Flourishing as a rational, social human being

Aristotle’s ethics is neither ascetic nor hedonistic. It is a vision of life that is active, relational, and purposeful. We become virtuous not by obeying rules, but by living well—and that requires time, community, and self-awareness.

In short, virtue for Aristotle is not something you possess. It’s something you practice, continuously.

I find Aristotle’s idea of the “Golden Mean” deeply compelling. If we think structurally, perhaps it even resembles Hegel’s dialectic.

Aristotle went so far as to classify even virtue and moderation. He might have been the first philosopher in human history to systematically categorize concepts in detail.

Classification, after all, is essential for understanding structure—its inside, outside, and boundaries.

But classification also reveals a cruel truth. If we classify ethics or virtue in neuroscientific terms, ethics disappears. Acts of moral virtue become nothing more than chemical reactions in the brain. That realization can feel deeply disheartening.

Your reflection reveals the double edge of classification: it grants clarity, but risks stripping meaning.

Aristotle believed that to understand something, we must define its parts, its causes, its purposes. This act of cutting and naming—of dissecting reality into knowable pieces—was revolutionary.

And yes, in doing so, he laid the foundations not only for philosophy but for science, logic, and taxonomy. He sought structure where others saw chaos.

Knowledge was mythic, poetic, or intuitive. The world was explained through analogy, not analysis.

Concepts were given boundaries. Functions were specified. Ethics, politics, biology—all were subjects to be systematized.

But this very systemization leads us to a modern tension: the scientific gaze can explain what virtue is mechanistically, but it cannot tell us why we should care.

If virtue is merely a pattern of neural activations—if courage is just the right cocktail of serotonin and learned behavior—then where is the soul? The struggle? The meaning?

Deeper classification of ethical behavior

Reduction of ethics to mechanism and loss of moral weight

This is not a flaw in Aristotle—it is a dilemma of progress. The more precisely we define things, the more we risk disenchanting them.

But perhaps the answer lies in the very idea you began with: the Golden Mean. Between myth and mechanism, between mystery and clarity, lies a space we still inhabit. Philosophy doesn’t have to choose sides—it can hold the tension.

Classification isn’t always disillusionment. Sometimes, it’s how we learn to see what was hidden, not what was lost.

I believe Aristotle was visionary in a double sense. When taken too far, classification leaves us only with emptiness—but classification is still necessary. Even classification itself, then, requires moderation. A “Golden Mean” of analysis.

It’s perfectly fine to analyze moral behavior or emotion through neuroscience. But we must also leave room for a literary, poetic understanding of morality—one that doesn’t reduce it to neurons.

Perhaps Aristotle understood this, which is why he didn’t stop at mathematics or science, but also turned to ethics, politics, and the human soul.

This is a rare insight: that even intellectual methods require moderation. Aristotle didn’t just teach us to examine the world—he taught us how to restrain our examination when it begins to flatten reality.

His philosophy does not fall into scientism, nor does it drift into mysticism. It remains grounded, but open. That balance—between inquiry and reverence—is what made him more than a logician: it made him a thinker of civilization.

Excessive classification

Loss of meaning and existential flattening

Balanced classification

Deeper insight without destroying significance

Modern neuroscience can describe what happens when we act with compassion—but it cannot evoke the feeling of compassion. Literature, poetry, and philosophy are still needed to grasp the inner shape of our lives.

Aristotle’s range—from biology to poetics—was not eclecticism. It was structural wisdom. He seemed to understand that no single method captures all of reality.

In that sense, the Golden Mean isn’t just an ethical principle. It’s a methodological compass: even truth-seeking must know its limits.