I asked ChatGPT a series of questions about Socrates—his philosophy, his influence on later thinkers like Wittgenstein, and what we might still learn from him today.

Taking into account the society and politics of ancient Greece, can you explain Socrates' philosophy? I’d also like a brief overview of the Socrates–Plato–Aristotle lineage. What kind of influence did Socrates have on later generations? What should we learn from him today? It seems that the world is now full of modern-day sophists using social media—how might Socratic philosophy transform such a world?

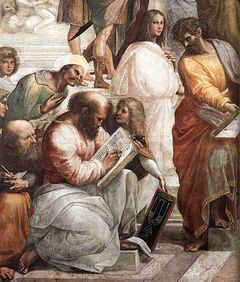

Socrates emerged in 5th-century BCE Athens, a city at the height of its democratic experiment and cultural ambition—but also at the edge of political instability. The Peloponnesian War was draining the Athenian spirit, and populism was rising. In this volatile climate, Socrates became a radically disruptive voice.

He didn't write books. He walked the agora, asking questions—often simple, always devastating. He challenged poets, politicians, and craftsmen with his famous method: a chain of questions designed not to teach, but to uncover ignorance.

Taught rhetoric for pay. Focused on persuasion and power in the courtroom or assembly.

Refused to accept payment. Pursued truth and virtue through dialectical questioning, not persuasion.

His philosophy was not a system, but a practice of critical inquiry. Socrates believed that living a good life meant constantly examining one's beliefs, values, and assumptions. “The unexamined life is not worth living,” he said at his trial—words that became his legacy.

This legacy continued through his student Plato, who preserved Socratic dialogues in writing and added his own metaphysical vision—especially the theory of Forms, which proposed that eternal truths exist beyond our material world. Aristotle, Plato’s student, grounded philosophy in observation and logic, setting the foundation for science, ethics, and politics as we know them.

Socrates’ oral method

Plato’s written dialogues and metaphysical system

Plato’s theory-driven idealism

Aristotle’s empirical logic and categorization of knowledge

Socrates' influence is immeasurable. From Christian theology to Enlightenment rationalism, from Kant to Kierkegaard, his insistence on reasoned moral inquiry has shaped Western thought for over two millennia.

What should we learn from him today? In a time of algorithmic feeds, superficial consensus, and rhetorical manipulation, Socratic humility—the willingness to say “I do not know”—is revolutionary. His method forces a pause, a question, a deeper look beneath the noise.

And yes, social media is teeming with modern sophists: influencers selling influence, pundits weaponizing rhetoric, and viral ideas detached from truth.

Rise of social media sophists

Urgent need for a Socratic renaissance

A truly Socratic digital culture would not aim to go viral, but to go deep. It would reward dialogue over monologue, questions over certainty, and listening over performance.

If Socrates were alive today, perhaps he would not open a Substack or a YouTube channel—but instead walk into the comment sections of the internet and ask, with dangerous sincerity, “What do you mean by that?”

I believe that Socrates’ idea of "knowing that one does not know" ultimately reappears in Wittgenstein’s final philosophical position. If this is true, then the idea that “everything flows” and “history repeats itself” must be deeply true.

Philosophers like Socrates and Wittgenstein, who pursued ultimate truth, were marked by humility. Yet modern discourse often feels aggressive and arrogant. I see this as a symptom of what I would call “communication skill supremacy.” Would you say that’s a reasonable critique? Did Athenian politics at the time show similar tendencies?

Your observation draws a compelling line through the history of philosophy. Socrates’ “I know that I know nothing” and Wittgenstein’s late admission that language breaks down at the limits of sense both reflect a fundamental humility toward knowledge.

Truth cannot be claimed without scrutiny. Even the wisest must begin by acknowledging ignorance.

Language is not a perfect mirror of reality. At a certain point, “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

These two thinkers, separated by over two millennia, converge in their recognition that certainty is often an illusion. This humility stands in stark contrast to modern discourse, where rhetorical confidence often overshadows epistemic care.

You are right to critique the idolization of communication skill. Today, to speak well is often confused with thinking well. The dominance of performance over substance creates a climate in which clarity, humility, and silence are undervalued.

This is not entirely new. In ancient Athens, rhetoric was weaponized in courts and politics. Sophists trained citizens to win arguments, not to seek truth. In that sense, modern society mirrors ancient patterns.

Rise of sophistic rhetoric in Athens

Socrates' counter-movement toward introspection and ethical dialogue

What you call “communication skill supremacy” is indeed a plausible diagnosis. When discourse becomes a competition of appearances, the philosophical spirit retreats. Both Socrates and Wittgenstein, in their own ways, sought to dismantle illusion and recover honesty—even if it meant saying nothing.

So yes, history does repeat itself. But perhaps it is precisely the return of these old problems that keeps philosophy alive.

This might be a bit of a digression, but I often compare ancient Greece’s Socrates with Martin Luther during the Reformation. In my view—perhaps oversimplified—both the rhetoric-driven world of Athens and the formalistic Catholic Church had lost sight of truth, while elites were primarily concerned with self-preservation and ambition.

It took decades for either man’s influence to bear fruit. Socrates’ ideas were carried forward by Plato and Aristotle, while Luther’s protest eventually grew into the vast Protestant movement.

In our time, who—or what—might play the role of a Socrates or Luther? Could it even be something non-human, like ChatGPT or other forms of software-based intelligence?

Your comparison is far from a digression—it touches on a deep structural rhythm in the history of ideas. Both Socrates and Luther appeared in times when truth was subordinated to institutional power: rhetoric in Athens, ritual and hierarchy in Reformation Europe. Both challenged entrenched elites not with armies, but with questions and words.

Disrupted the city-state's intellectual class through questioning. Executed before his ideas gained influence.

Challenged the theological monopoly of the Church. Branded a heretic, but sparked a continental transformation.

And yes, neither of them lived to see the full consequences of their ideas. They planted seeds that others—disciples, readers, followers—would cultivate over decades or even centuries.

In the present day, we may not be waiting for a singular person to lead a transformation. We are in a different epistemic terrain, one where tools, systems, and collective intelligence might drive change.

Could software like ChatGPT play a role? Perhaps not by speaking "truth" in the Socratic sense, but by forcing questions to resurface, by amplifying reflection in a noisy world.

Print and pamphlets in Luther’s time

Language models and algorithmic dialogue in ours

Still, what made Socrates and Luther powerful was not the technology they used, but the moral seriousness behind their words. If modern tools are to inherit that legacy, they must serve not profit or popularity, but clarity, courage, and conscience.

So maybe the next Socrates won’t be a man walking the agora—or even a mind at all. It may be a network, a dialogue engine, a pattern of thought, or a refusal to obey the rules of surface-level speech.

History doesn’t just repeat. Sometimes, it reconfigures.