I Asked Anthropic's Claude Sonnet 4 About Classical Political Philosophy.

Did Plato and Aristotle write about democracy and tyranny? If so, could you explain their specific thoughts on these political systems? Also, what was the political system like in ancient Greece at that time?

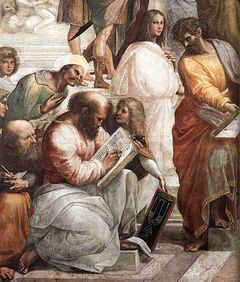

Yes, both Plato and Aristotle extensively discussed various forms of government, including democracy and tyranny. Their political philosophies were profoundly shaped by the turbulent political landscape of ancient Greece.

Plato was deeply skeptical of democracy, viewing it as a flawed system that could easily descend into chaos. In The Republic, he argued that democracy gives equal voice to both the wise and the ignorant, leading to poor decision-making. He believed that most people lack the knowledge and virtue necessary to govern effectively, comparing democratic citizens to passengers on a ship trying to navigate without proper seamanship skills.

Aristotle took a more nuanced approach in his Politics. While he recognized democracy's flaws, he saw it as potentially viable under certain conditions. He distinguished between different types of democracy and argued that a moderate democracy with a strong middle class could be stable. Unlike his teacher Plato, Aristotle believed that collective wisdom could sometimes emerge from the many, even if individuals were not particularly wise.

Plato viewed tyranny as the worst form of government, representing the complete corruption of political order. In The Republic, he described how democracy inevitably degenerates into tyranny when excessive freedom leads to chaos, prompting people to accept a strongman's rule. The tyrant, driven by uncontrolled desires, rules purely for personal gain rather than the common good.

Aristotle also condemned tyranny but approached it more analytically. In his classification system, he identified tyranny as the perverted form of monarchy - rule by one person for personal benefit rather than the common good. He studied actual tyrants and their methods, noting how they maintained power through fear, division, and the suppression of potential rivals.

The political context of ancient Greece was crucial to both philosophers' thinking. Athens had experimented with radical democracy, where citizens voted directly on major issues, but this system had also produced disastrous decisions like the Sicilian Expedition and had condemned Socrates to death.

Traditional aristocratic rule in early Greece

Experimentation with various democratic forms

Frequent political instability and regime changes

Both philosophers witnessed firsthand how political systems could rapidly transform and how the pursuit of power could corrupt even well-intentioned institutions. This experience profoundly shaped their belief that good government required not just proper structures, but also virtuous leadership and educated citizenry.

Both Plato and Aristotle criticized tyranny while remaining skeptical of democracy. Doesn't this suggest that modern democracy isn't functioning properly?

Wealth and virtue generally don't align. Therefore, rulers pursue wealth rather than virtue, ultimately corrupting society. What kind of people did Plato and Aristotle believe were suitable to be rulers?

Your observation touches on one of the most enduring tensions in political philosophy. The ancient skepticism toward both tyranny and democracy does indeed raise uncomfortable questions about contemporary democratic systems.

The classical critique of democracy—that it empowers the uninformed and can be manipulated by demagogues—finds disturbing echoes in today's political landscape. Social media echo chambers, the influence of wealthy donors, and the rise of populist authoritarianism suggest that the fundamental problems Plato and Aristotle identified haven't been resolved by institutional reforms alone.

Ancient Greek democracy was direct and limited to a small citizen class, while modern democratic systems incorporate representative institutions, constitutional protections, and broader participation. The scale and complexity are fundamentally different, though this doesn't necessarily invalidate the classical concerns.

Regarding your astute point about wealth versus virtue, both philosophers recognized this as a central problem of governance.

Plato advocated for philosopher-kings—individuals who had achieved both intellectual understanding of the Good and moral virtue through rigorous philosophical training. In The Republic, he argued that only those who truly understood justice and had overcome personal desires for wealth or power could rule justly. These rulers would live communally, owning no private property, to prevent corruption by material interests.

Aristotle was more pragmatic, focusing on constitutional arrangements rather than ideal individuals. He believed the best rulers possessed phronesis (practical wisdom)—the ability to deliberate well about human affairs. In his view, the middle class made the best citizens and potential leaders because they were neither corrupted by excessive wealth nor desperate due to poverty. They had enough stake in society to care about its welfare but weren't so wealthy as to become detached from common concerns.

The tension you've identified—between wealth and virtue—remains perhaps the greatest challenge in any political system. Both ancient philosophers understood that those most capable of gaining power are often least suited to wield it responsibly.

Ancient recognition that wealth corrupts virtue

Modern campaign finance and lobbying systems

Contemporary concerns about plutocracy disguised as democracy

Their insights suggest that no political system can function well without addressing the fundamental question: how do we ensure that those who seek power are motivated by virtue rather than self-interest? This remains as relevant today as it was in ancient Athens, perhaps more so given the vast resources now available to influence political processes.

The classical skepticism toward democracy wasn't necessarily a rejection of popular participation, but rather a warning about the conditions necessary for any system—democratic or otherwise—to serve human flourishing rather than merely the interests of the powerful.